The war in Sudan affects the surrounding countries of the Sahel region, for which the country is an important cultural and economic centre. Today, Chad is struggling with armed war returnees, social tensions and restricted trade routes.

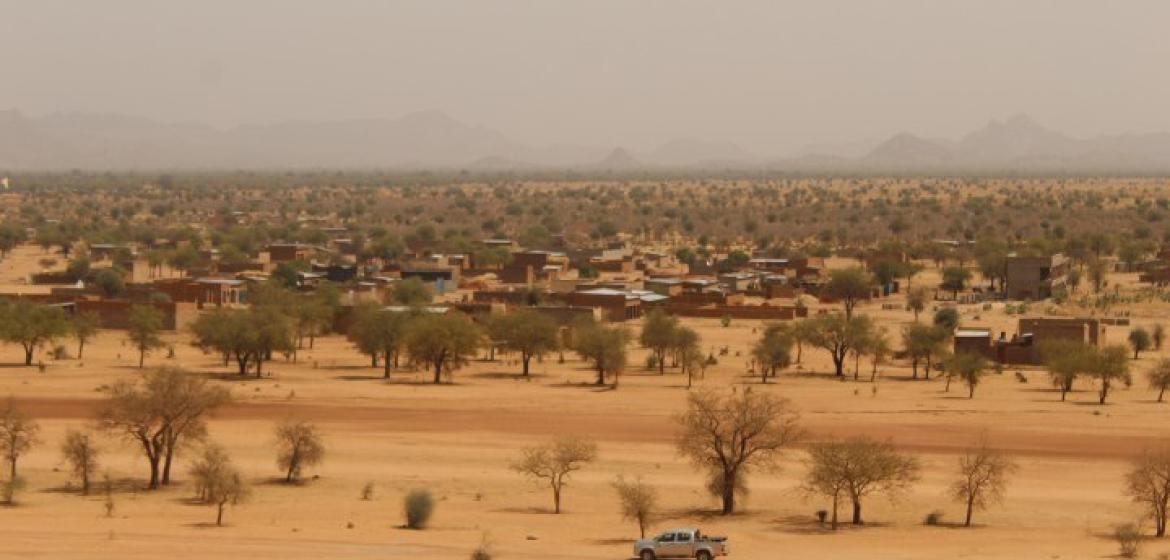

Like most regions of the Sahel, large parts of the central Chadian Guéra province are inhabited by a complex social fabric of communities identifying with different languages, religions, and lines of ancestry, some of them summarized under the name of “Hadjerai”. Asking a Hadjerai friend about their neighbouring tribe of the Abbala — whose camels were seasonally grazing close to some of the Hadjerai villages at the feet of the Guéra Massif — Bechara* answered that he would say they have an overall good relationship with their nomadic neighbours. Nevertheless, he explained that the “Arab” community, that he himself does not belong to, had recently lost a lot of their male children to the war in Sudan, as many were recruited to fight for the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). While some reportedly returned after months of warfare and plundering, others never came back, leaving their families with nothing but the grief over their lost children.

With Guéra being in a distance of more than 500 km from Sudan’s westernmost border, this shows the multiple connections between the two Sahelian countries. They also become visible in the daily accounts of Chadians who are not only observing the war from afar but who are directly or indirectly affected by it and its broader consequences for the region. Acknowledging this requires broadening our understanding of Sudan’s political and cultural impact in a wider Sub-Saharan context — and to rethink the boundaries of the WANA region.

While Sudan is already frequently excluded from conceptualizations of the “Arab world”, other Sub-Saharan Arabic-speaking countries, such as Chad, are often entirely overlooked in political analyses and international media coverage – let alone in discussions of interconnectedness or cross-border dynamics.

Spillovers of the War

As a sharp contrast to that, even in the dusty Chadian capital of N’Djamena, located far west from most other parts of the country, at the shores of the Chari River, the war in Sudan is quite tangible. Ordinary people are attentively following the cyclical waves of warfare of their eastern neighbours, commented on by political analysts and sympathisers of both the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the RSF on social media. From their perspectives, fears of the war in Sudan spilling over into Chad are more than a far-fetched possibility when referring to past experiences of the 2008 rebel attack on N’Djamena. These rebellions originated in the far east of Chad, and were directly supported by the Sudanese government of Omar al-Bashir at that time.

Furthermore, the current war is also felt through disrupted supply chains for imported goods like sugar, as well as an increasing pressure on cereals and items of daily use. Many Chadians complain about the soaring inflation. Exacerbated by the additional millions of people who had escaped the ethnically motivated violence in Darfur over the last three years. Long lines of trucks heading east can nowadays be observed on the outskirts of N’Djamena, delivering goods to the refugees from as far as the ports of Douala in Cameroon. But the resurging war is not the only context in which a certain interconnectedness becomes visible.

Sudan as a regional epicentre

In the central parts of Chad, cultural, economic and religious ties with Sudan are even closer. More than the mutually competing political regimes in Chad and Sudan, a feeling of shared identity and culture persists. A feeling that is partially expressed in the presence of Sudanese comedians displayed on the blurry screens of coaches and older men sitting on woven plastic mats while listening to the tunes of renowned Sudanese artists such as Abdelkarim al-Kably, Mohammad Wardi and Abdel Gadir Salim. For people inhabiting those areas of Chad, the western regions, including N’Djamena, have hardly been a destination for travel, commerce, or migration. Unlike cities such as Massenya and Abésché in the central and eastern parts of the country, which historically originated as capitals of the precolonial Baguirmi and Wadai Sultanates, the Chadian capital was only founded under French colonial rule. For a long time, it did not offer much attraction to many Chadians due to its relative remoteness and lack of infrastructure.

Decades before and even after independence, the primary destination of migration for many arabophone people in central and eastern Chad was Sudan, where they went for pilgrimage, commerce, medical treatment, and education. This may have partially changed with increasing infrastructural development, connecting the eastern provinces of the country with N’Djamena. But neither this material development nor the ideological power of post-independence Chadian nationalism in connection with repeated cross-border conflicts disrupted the strong connections between the neighbouring countries.

Trans-Sahelian Mobility

Close cultural, economic, and religious ties between large parts of central and eastern Chad with Sudan are therefore often leading to a perceived closeness of the Sudanese conflict among many people in the region. This is not only the case in Chad but also in South Sudan and Eritrea, which share certain political and economic ties with the country. Those countries host large diaspora populations that interlink them with each other, Arab and non-Arab groups.

Trans-Sahelian mobility as of late became visible when Chadians returned to their western hometowns during or after the outbreak of the war in Sudan. Among them is Aboubakar who, at the time of writing this article, had just recently returned from Sudan, where he worked at a cattle market on the outskirts of Omdurman. He is talking about the hardships involved in crossing the whole country, while returning to his small hometown in the rural areas of the central Chadian Guéra: “When I crossed the border, alhamdulillah, I thought, I was finally safe”.

Increasing conflicts

But this is not the case for all returnees. Not far from the region where Aboubakar returned to, at the easternmost prefecture of the central Chadian Guéra province named Mangalmé, a conflict had shaken the unstable foundation of the region’s multiethnic population cohabiting peacefully. In 2022 and 2023, an armed struggle between some of the largely nomadic Arabs — often heavily armed after returning from the fighting in Sudan — and the sedentary Mubi of eastern Guéra had arisen, centring around land rights and access to grazing areas. It caused several hundred deaths among both communities and rendered parts of the region a no-go area.

Rethinking the WANA region

Yet what do these small examples reveal about the significance of the so-called war of generals in Sudan for its neighbouring countries? First, the war has made Sudan an epicentre of destabilisation in a region, located on the borders of the “Arab world”. This role draws from Sudan’s relatively large Arabic-speaking population and economic wealth (compared to Eritrea, Chad, and South Sudan) but also its cultural soft power. These factors position Sudan — and the currently unfolding war — in a centre within the margins.

The second learning might be a need for increased inclusion of the Arabic-speaking parts of Sub-Saharan Africa in the Global North when speaking about recent political events in the WANA region. While many countries of the Sahel region like South Sudan, Eritrea and Chad and many more are seldomly considered part of WANA, they nevertheless bear many ties to it. These ties are expressed not only linguistically but also politically, economically, and militarily. Through the implications of the Sudanese war, some of these ties have become increasingly visible in Chad, a country where around 20 percent of the population speaks Arabic as their native tongue, and a further 40 percent speaks it as their second language.

In this extended WANA region, Arabic is far more widely spread than often acknowledged, with Sub-Saharan varieties of Arabic centring largely around Sudan. This is one reason why, for many of its neighbours, Sudan is perceived as the heart of a Sub-Saharan Afro-Arab region. As this centre is currently enduring a bloody and brutal war, the spillovers of the conflict threaten and destabilise far larger parts of the region. Up to this point, some consequences of this interconnectedness have begun to destabilize South Sudan. The country is on the brink of civil war, while Sudanese generals threaten to attack Chadian airports in Amdjarass and N’Djamena. At this point, we should ask: From which perspective can Sudan be considered marginal?

* name was changed