Delivery workers around the world have had enough. In Lebanon, they have started to organize themselves and went on strike against the local delivery app Toters. Their exploitation is systematic and builds on the Kafala system.

Each day, a delivery driver in Lebanon makes an average of 20 to 25 trips. Road conditions are often dangerous, and salaries do not cover their basic needs. Once employed, the delivery worker has to pay for a previously used uniform, the company’s delivery bag, for a motorbike they use for deliveries and repairs. On top of that most delivery orders are paid in cash, increasing the delivery workers’ risks: If they are robbed, the company does not cover any costs and delivery workers have to compensate the stolen amount. Typical work conditions in the so-called gig economy.

What is the gig economy?

Delivery apps are part of the gig economy, a digital platform-based model that is advertised as a “flatter and more participatory” model and as the ideal replacement for traditional business models. Platform workers around the world are employed as “independent or remote contractors”. They are called “micro-entrepreneurs” or “self-employed”. Their work is mediated through a series of algorithms, usually centralized around an online app that is also used by customers who employ their services.

Toters, the biggest Lebanese Delivery app sells the system as follows: “We offer drivers the ability to come get trained and have a new way to earn money and have full flexibility on whether or not they would like to work.”

At first sight, this reclassification of labor may appear as a positive development, enabling greater social mobility. In reality, this reclassification strips platform delivery workers of their fundamental rights, such as their right to health and insurance benefits, to form unions, and a plethora of other workers’ rights. As the hierarchical nature of traditional management is shunned and deplored as outdated and obsolete, so are the rights acquired against it.

The gig economy is powered by migrant workers

Migrant workers are at the centerpiece of these platforms, representing most of the workforce. In recent years, the supposedly flexible employment contracts and hiring procedures of the gig economy have attracted a growing number of migrants throughout the world, especially in cities in India, Bangladesh and China. In these countries, the gig or platform economy relies primarily on internal migrant workers, who often move from rural areas to major cities. There, they provide gig economy services such as ride-sharing, food delivery and domestic and care work. This development indicates that without a continuous influx of migrants, platform companies would be unable to provide their services at the cut prices they can offer today.

So, if the platform economy provides thousands of jobs should we consider their exploitation as a “small price to pay” for the opportunity to pull themselves out of poverty?

This argument has been deployed against workers since the rise of capitalism, highlighting that the only freedom under capitalism is the freedom to be exploited, albeit nowadays under algorithmic management.

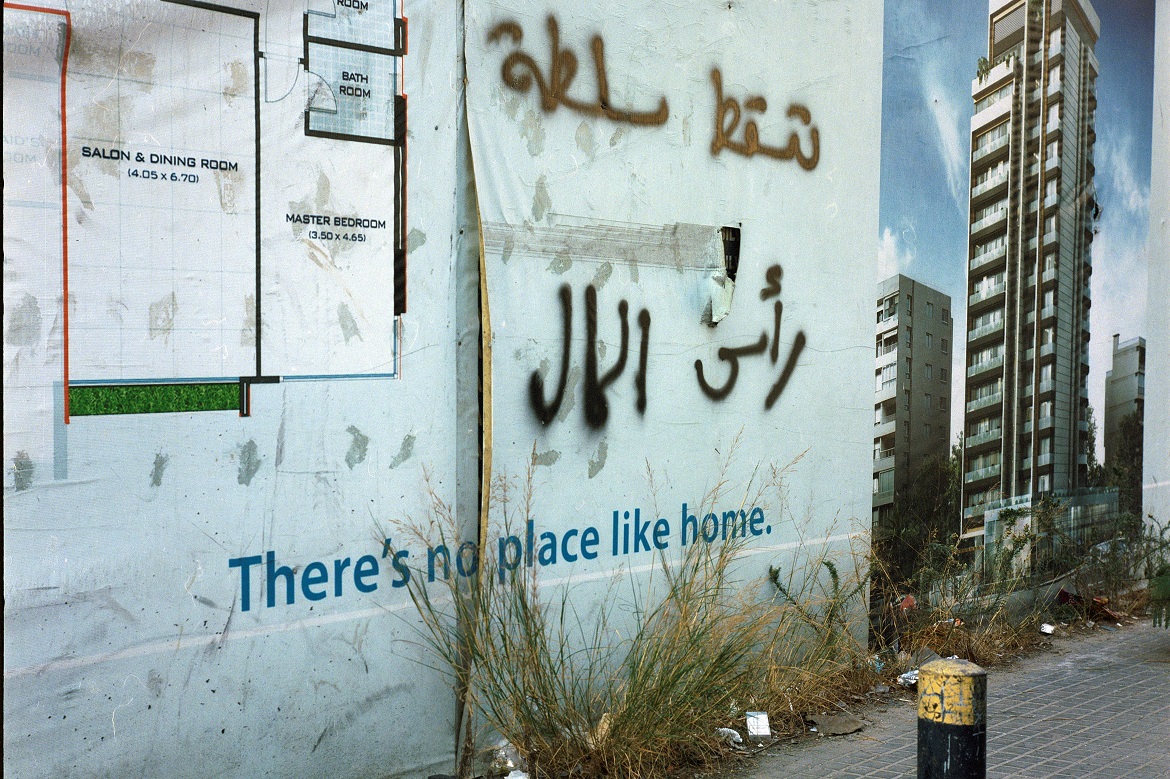

The case of Lebanon

Lebanon is a microcosm of today’s capitalist contradictions. The recent financial dispossession ravaged a socio-economic and financial order that was believed to be infallible. Centerpiece of the dispossession is a network of politically and economically influential figures who are deeply invested in the viability of the banking sector. The Lebanese economy has always stood on the labor of thousands of migrant workers. For decades, they have been hyper-exploited and precarized, creating a reserve army of labor.

The Covid-19-pandemic has further worsened their socio-economic conditions and has simultaneously opened up the market for capitalist opportunists. The gig economy has been profiting from a downwardly-mobile middle class and a precarious migrant labor force. Delivery-based grocery stores boomed during the pandemic because supermarket chains were still wedded to their old profit margins and opened an opportunity for smaller delivery-based stores. The gig economy’s work force mainly consists of those Lebanese, Syrians and Palestinians who were unable to flee the economic crisis in Lebanon – and it is them who started organizing.

Toters, the Kafala-App

Toters is doing well: In June 2022, it was reported that its owners raised more than 15 million US-Dollar in funding from International Finance Corporation (IFC), March Holding, and BY Venture Partners. One of Toters’ co-founders, Tamim Khalfa, is a Syrian-born, Saudi-raised Canadian entrepreneur and former systems engineer. In 2011, he shifted to management consulting, where he met his co-founder Nael Halwani. By his own admission, Khalfa’s financial acumen is derived from his willingness to ignore the financial industry's “risk aversion towards countries that have a challenging macroeconomic and political profile” like Lebanon. He is thus betting on taking advantage of a large section of migrant workers, who are easily disciplined into low wages by the Kafala system.

As elsewhere, the gig economy has built up their businesses on existing labor arrangements and relations: In the case of Lebanon, this is the Kafala or sponsorship system. As explained by feminist sociologist Amrita Pande, the Kafala system in Lebanon delegates the structural problem of workers and immigrants’ rights violations to private households, while producing a population of easily exploitable workers.

The customer's responsibility

Gig workers are expected to run as efficiently as software and technology. Precarized migrant workers are not only pegged against each other, they are also in competition with an imagined ideal of a delivery worker. This leads to a built-in unevenness between software-calculated demands and the constraints a human delivery worker is facing.

With platform economies, private households are not employers of these migrant workers, but their and the App’s customers. The shift from traditional business management models to algorithms is now placing the responsibility on the customers. Customers support the system every time they report workers for delays, misbehavior, or the general quality of the food. Every click, rating and incendiary review ideologically binds customers to algorithmic management and steers them away from treating migrant delivery workers as equal human beings.

Many companies use scores, extra points, and customer feedback to nudge workers in ways that the companies prefer. Surveillance and disciplining that can change the driver’s livelihood, are turned into online games. Gamification is a technique of turning labor into a series of tasks that can be completed like a game.

This process is neither new nor is the gig economy the only industry applying it. The delivery app only accentuates and digitizes what the Kafala system has institutionalized. The app does not obfuscate class and race relations, but highlights them. It tries to connect to the customer’s history of exploiting and disciplining workers through the Kafala system.

Toters delivery workers strike back

The drivers´ first strike in October 2021 took place in front of the company´s headquarters and was met with armed mercenaries sent by the management of Toters. The workers went on strike since, amidst fuel rationing and power cuts, they are often refused pay if the order is canceled by customers.

As mentioned above, delivery (app) workers are classified as “independent contractors” under Lebanese labor law, having no access to social security or health benefits and with the employer being able to lay them off any time. Their company´s management considers them expendable, “unskilled” and easily replaceable. Therefore, the management increased the surveillance and crackdowns of workers trying to organize themselves. When some Toters riders formed groups on WhatsApp and created Instagram pages to share their grievances to float the possibility of strike action, Toters higher management deactivated their accounts, and barred them from working until they removed the posts.

Despite the repression, Toters delivery workers held two more strikes in February 2023. Toters charges customers 90,000 Lebanese pounds (LL; about 0.80 euros according to the exchange rate of the Toters-App)[1] per delivery. Of this, only a little more than half goes to the drivers, the rest goes to Toters. Drivers demanded that the fee is disclosed to them and that they get paid the full amount that the customer is being charged. Again, the strikes were met with repression and organizers and leaders of the movement had to go underground.

These conditions have rendered delivery workers one of the most exploited groups of the precarious working class in Lebanon but have also opened up opportunities for organizing. Even if banned for now, mutual aid networks on Social Media and continuing strike actions gave a glimpse into their growing resistance.

[1] As of 07/13/2023. The prices and also the exchange rate set by each operator vary greatly. The official exchange rate does not correspond to the rate used locally.