History and geography play a big role in Hebron, also referred as the Israeli-Palestinian flashpoint. Walk down memory lane with me through Hebron and follow Izzat Karaki, a Palestinian activist at Youth Against Settlements (YAS).

Hebron is one of the oldest inhabited cities in the world. It’s the second largest city in the West Bank and its economic center, with lots of handcrafted production based in the area, selling Palestinian products. Here you can find markets, three universities and a college. But what’s making Hebron’s uniqueness is something else: Hebron is the only city in the West Bank where there are Jewish settlements and settlers in its core.

Amnesty International and other NGOs have defined Israels occupation and colonization regime in the West Bank as apartheid. In this text, concepts such as apartheid, colonialism and colonization occur. You can find our explanations and their use and meaning in the German context here (in German only).

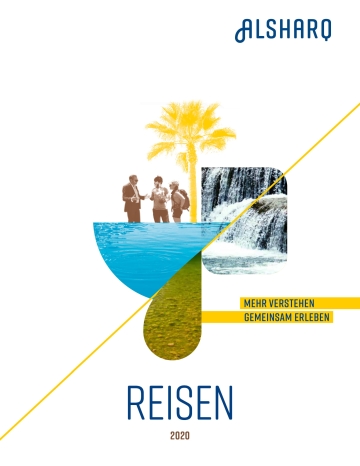

“In 1997, an agreement between the PLO and Israeli government divided my city in two parts: H1 and H2. H1 makes out 80 percent of the city and is under Palestinian authority, H2 counts for 20 percent and is under Israeli military control“, says Izzat. He explains that the H1 area is completely Palestinian while the H2 area has a mixed population consisting of Palestinians and settlers. However, Izzat specifies that “the settlers and us, we are not equal by law. Me, as a Palestinian, I am under Israeli military law and the Israeli settlers are under Israeli civil law. It means that as a Palestinian I am always guilty until proven innocent, but the settlers, they are innocent until proven guilty”. The latter never happens.

The tour takes us through the Old City, the city center which is located in the H2 zone. We have to go through multiple checkpoints: the IDF is asking for my passport and Izzat’s green ID. We are passing IDF soldiers, Jewish settlers, tourists from all around the world and Palestinian shopkeepers and kids playing on the streets.

Part One: The settlements

There is four older settlements in the city of Hebron: Kiryat Arba was established after the war in 1967. It’s one of the biggest settlements in Hebron with around 8,500 settlers right at the outskirts of the city. The other three are in Hebron’s center. Among them is the Beit Hadassah settlement, which was founded in 1979.

The other two were established at the beginning of the 1980s. “Beit Romano used to be a school called Osama Ben Munqez, my father used to go there when he was younger“, remembers Izzat. “Right after the Israeli occupation in 1981, the building was changed into a yeshiva school.” The settlement Avraham Avinu is right in the middle of the Old City. Settlers have been occupying and living in Palestinian houses above the marketplace for over 40 years. It’s a tight cohabitation: two snipers are positioned 24/7 on neighboring Palestinian rooftops to purportedly protect everyone. But for the trash, acid and urin settlers throw onto the market street where Palestinians shop, walk, sell and spend time, no one will be held accountable for. “Those snipers are only there to protect settlers from Palestinians, when it’s them attacking us, nothing ever happens. No one will protect us Palestinians from settler violence“, explains Izzat. According to him, this is due to the fact that “settlers and soldiers come from and bring the same ideology to the West Bank in order to colonize it.“ Many soldiers become settlers themselves and would never turn against each other.

The last settlement is the one behind the YAS-House located in Tel Rumeidah. “First, it was made an Israeli military base, after that, they brought in the settlers“, the YAS-activist says. “That’s one of their techniques: taking the land, purportedly for security reasons, militarize it and then bring in civil people who become settlers. Now, at the back of our house we have a big settlement, they call it Ramat Yishai.”

All the buildings settlers are living in what used to be Palestinian spaces of public life like schools, hospitals and hotels.

Settling and settlements in the West Bank are illegal under international law which also includes their expansion on Palestinian land. The settlers’ (and Israel's) underlying goal is to evacuate all Palestinians from their land and their city, in order to connect all the settlements to create an Israeli settler town in the middle of Palestine. They do this by military occupation: first areas are militarized, then settlers are infiltrated.; by squatting: Zionists stay in hotels and then refuse to leave, backed up by Israeli soldiers and by strategic closure of streets. All in all, this makes the lives of the Palestinians unbearable: settler violence, IDF violence, water and electricity shortages, mass surveillance, no free movement, no hospitals, no passing through for ambulances, not enough schools nor kindergartens.

The Israelis plan is to build more and more settlements in the Old City of Hebron. Shuhada street located in the H2 zone (circled in bright blue on the map) is their newest project and the fifth settlement in Hebron. “They built a new settlement right there on land belonging to the Hebron municipality, without asking, without paying, without caring about anyone but themselves. They’ll always want more, and thus occupy or close off further areas to Palestinians in order to put more and more settlers in.”

Part Two: Shuhada Street

“It used to be one of the most important streets in Hebron, it used to be the heart of the city. Nowadays, it’s completely closed, completely empty”, explains Izzat. It is also another example of the segregation happening in Hebron: Palestinians don’t have access to the street anymore, but everyone else does, be it Israelis, settlers, tourists, or soldiers. Izzat remembers that “in the old times, Palestinian flags hanging on the street would flutter in the wind, but eventually all there is to see now are Israeli flags.” Altogether Palestinian flags are banned by Israeli law in Hebron and raising one is punishable. “If you enter the city, you could never tell it’s Palestine, you wouldn’t notice that it’s Palestinians who live here.”

As the heart of the city, Shuhada street used to connect the North and the South of Hebron, but it has become a ghost street since its closure in 1994. Natives are prohibited from using the road, even to get to their shops or apartments. Therefore, more than 1,800 shops and more than 1,000 Palestinian apartments are empty. Izzat remembers: “All our life used to be here and now we are not even allowed to walk on it. There used to be gold shops, yoghurt, fruit and vegetable shops, a camel market, a chicken market and so much more. I remember all of it: when I was a kid, after school and lunch, I would go to the chicken market. I loved animals!”

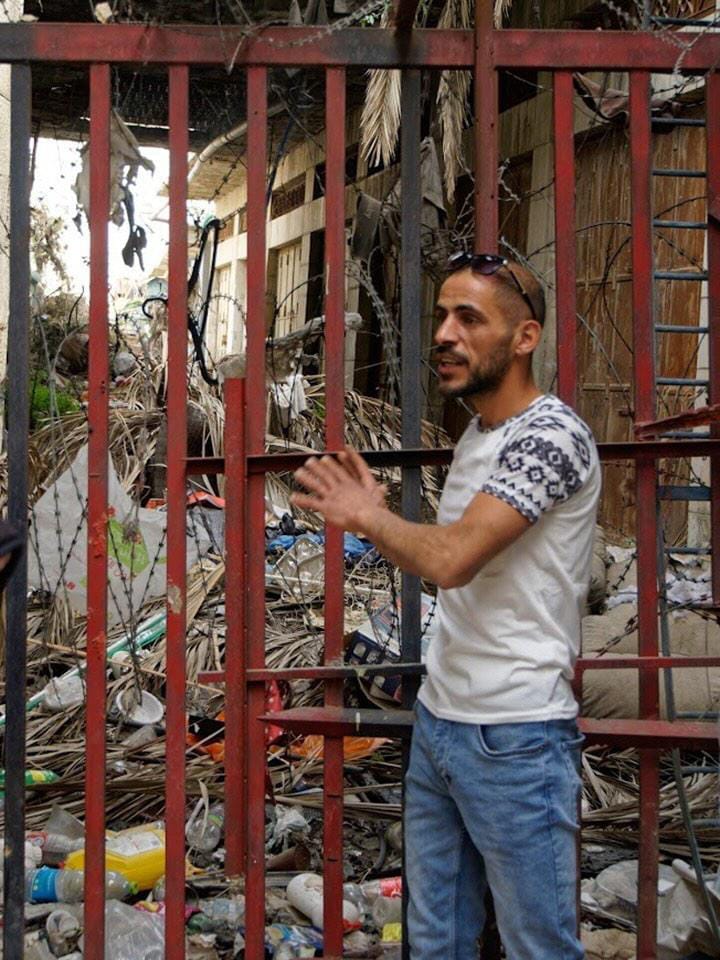

“The Gold Market used to be the most beautiful market. Now it’s the settler’s private landfill. They throw all of their trash there, no one is stopping them. There used to be 50 shops, but they were closed by military order and we can’t access it.” Palestinians risk being arrested or even being shot if they try accessing the area to clean it up.

“These few hundred settlers have more rights than us and have all their needs met. An organization called Hebron Fund based in Brooklyn, New York is covering the water and electricity bills, housing units, healthcare, education, transportation. Over time, they’ve collected millions upon millions specifically for the Jewish settlers living here in Hebron”, Izzat says.

In Shuhada street a few hundred settlers live in between 35,000 Palestinians. It accounts only for one square kilometer, but there are 22 checkpoints, more than 100 movement barriers and 120 watch towers with cameras. “For us, it’s not safe here, but we have a mission: remain in Hebron to protect this land, these houses, these shops from the Israelis and settlers. It’s our only way of resistance: to stay.”

Part Three: Ibrahimi Mosque

The Mosque is considered a holy site by Judaism and Islam. Also called Tomb of the Patriarchs, it is believed to be where Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and their wives Sarah, Rebecca and Lea are buried. During Herodian times, a protective rectangular enclosure was built on top of the cave supposedly containing the tombs. A Byzantine basilica was built on top; after the Muslim conquest it stayed a mosque for centuries before the Crusaders reconverted it into a church. It then became a mosque once again, but since 1994 it is stained with a touch of Israeli colonialism.

On February 25th, 1994, during Ramadan, an Israeli-American citizen, Baruch Goldstein, entered the Ibrahimi Mosque during prayer time, shooting and killing 29 Palestinians and leaving over 150 injured. The massacre was followed by clashes in the whole of Palestine that lasted three days and another six people died in Hebron. Goldstein was killed by survivors and could not face punishment, but the soldiers of the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF; commonly called Israeli Occupying Forces, IOF in Palestine) who were involved in the clashes were never held accountable, nor punished. Instead, the mosque was closed by the IDF and divided into two parts: one as a synagogue for the settlers which accounts 60 percent of the building and one as a mosque for the Palestinians Izzat adds that as a result of the Ibrahimi Mosque massacre, not only the mosque was closed, but also Shuhada street, the shops and whole Palestinian neighborhoods. “They punished us, the victims.”

“As a Palestinian, I cannot access the part of the mosque that was transformed into a synagogue”, explains Izzat. As part of an agreement settled in 1996, 10 days a year the whole building is closed for Palestinians due to Jewish bank holidays and on other 10 days a year, Palestinians can access the whole of the building. “But unfortunately, the Israelis and settlers don’t respect our mosque, they party, dance, put on loud music, drink alcohol inside and so on. They don’t care about the building being a holy place for Muslims.